Hair Manifesto

Hair Manifesto

2020 - 2022

Walker configures a series of works that successively prologue and

intertwine loss, death, trauma, and incantation through the hair of strangers

as well as her own. This interweaving is not metaphorical; it is knotted,

preserved in keratin, and solidified in porcelain, gold, and silver; it is

long-lasting, as is the visual impact of the pieces as a whole.

The nightmare of losing one's hair becomes a work of art; they are pieces that fall off, symbols of strength and vitality, which, when detached, reveal weakness, illness, and death. These are the adjectives the artist utilizes in her ecology of loss, from which she seems to affirm that there is nothing that cannot be translated into pain.

The artist weaves a part of her life with obsolete parts of her body. She creates objects that are time capsules for a future from which to defend herself. These memories will not be lost. As Gruzinski mentions in Images at War, these fields of experiential images that the artist has lived and lost will live forever in the material, in hair, and will grow even when the work is over as the hair of the dead grows even after their heart stops beating.

The exercise of loss and the process of weaving with the missing pieces is a practice that is inversely proportional to oblivion. This surgical exercise of measuring, counting, braiding, knotting, cutting, and enumerating hair - as if finding melancholic and dead meaning in the repetition of the action - is an elegy for something that expands its definition in death. We stand before an expansive mortuary work, which affirms that we are not amphibians and do not regenerate if a limb is amputated - except for our hair, since it holds our existence's archive and the record for accessing the life of our ancestors, their genetic material, their DNA.

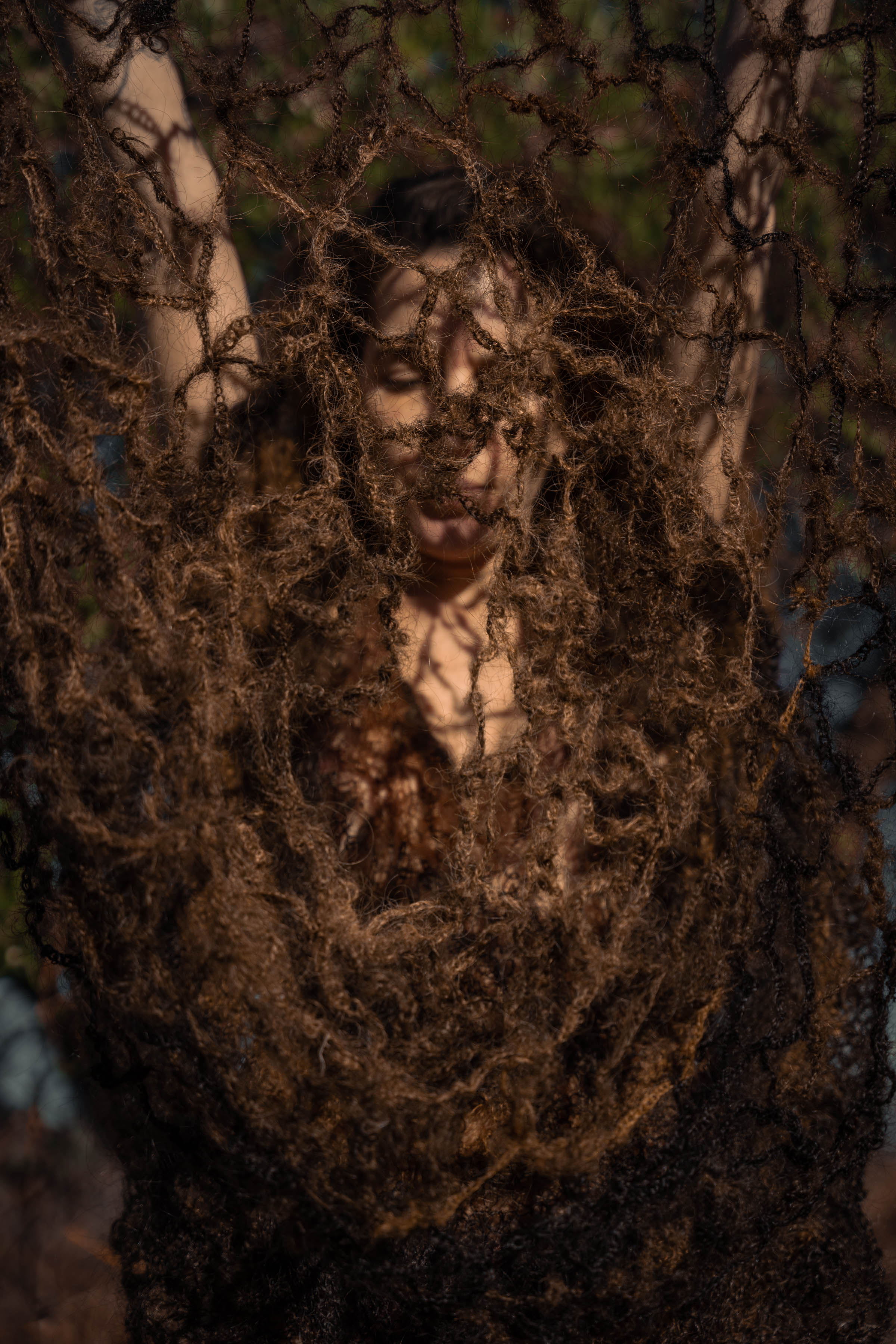

When Walker ties the knot on the back of a brooch or casts a clump of hair in ceramic, she performs a conjuration infused with mysticism related to her origin from the island of Chiloé. From the witch rituals of Chonchi to the Guatemalan quitapenas, these objects, filled with human genetic material, are good luck charms against the evil eye, violence, panic, and monstrosity; we witness something that works as a symbol: from the human hair protection sorcery that she performed to protect her friends, to the human hair masks and costumes, protection is born from the body itself. It is like a turtle's body, creating an armor with its own means, like an animal that creates a shield - made of hair - against danger. Hair is used as a mask to protect us from humanity or scare it away. Ominous eyes emerging from a clump of hair are reminiscent of the atavistic myth of the monster. The erotic darkness and the connection to terror reinforce a world's strange and intimate nature where Walker establishes her own rules, gods, and legislation against daily darkness.

The artist asked her friends for hair, and repulsion to fallen strands of hair gains a new meaning. In this technology of falling, Walker shapes a millenary pact, requesting genetic material to braid an image. She states a triple story: the subject to whom the hair belongs, their portrait, and biography. This diary of loss brings us closer to our quotidian pain as spectators. Walker creates a universal, atavistic story, and this is where her sensitive, humble and straightforward, recycled, sad, and painful nature lies.

As the artist mentions: "I try to submerge a little deeper with each knot, to sink into myself," in the most Jonas Mekas sense, to get lost for the sake of getting lost, even more with a thread of hair, that binds her to the world.

The nightmare of losing one's hair becomes a work of art; they are pieces that fall off, symbols of strength and vitality, which, when detached, reveal weakness, illness, and death. These are the adjectives the artist utilizes in her ecology of loss, from which she seems to affirm that there is nothing that cannot be translated into pain.

The artist weaves a part of her life with obsolete parts of her body. She creates objects that are time capsules for a future from which to defend herself. These memories will not be lost. As Gruzinski mentions in Images at War, these fields of experiential images that the artist has lived and lost will live forever in the material, in hair, and will grow even when the work is over as the hair of the dead grows even after their heart stops beating.

The exercise of loss and the process of weaving with the missing pieces is a practice that is inversely proportional to oblivion. This surgical exercise of measuring, counting, braiding, knotting, cutting, and enumerating hair - as if finding melancholic and dead meaning in the repetition of the action - is an elegy for something that expands its definition in death. We stand before an expansive mortuary work, which affirms that we are not amphibians and do not regenerate if a limb is amputated - except for our hair, since it holds our existence's archive and the record for accessing the life of our ancestors, their genetic material, their DNA.

When Walker ties the knot on the back of a brooch or casts a clump of hair in ceramic, she performs a conjuration infused with mysticism related to her origin from the island of Chiloé. From the witch rituals of Chonchi to the Guatemalan quitapenas, these objects, filled with human genetic material, are good luck charms against the evil eye, violence, panic, and monstrosity; we witness something that works as a symbol: from the human hair protection sorcery that she performed to protect her friends, to the human hair masks and costumes, protection is born from the body itself. It is like a turtle's body, creating an armor with its own means, like an animal that creates a shield - made of hair - against danger. Hair is used as a mask to protect us from humanity or scare it away. Ominous eyes emerging from a clump of hair are reminiscent of the atavistic myth of the monster. The erotic darkness and the connection to terror reinforce a world's strange and intimate nature where Walker establishes her own rules, gods, and legislation against daily darkness.

The artist asked her friends for hair, and repulsion to fallen strands of hair gains a new meaning. In this technology of falling, Walker shapes a millenary pact, requesting genetic material to braid an image. She states a triple story: the subject to whom the hair belongs, their portrait, and biography. This diary of loss brings us closer to our quotidian pain as spectators. Walker creates a universal, atavistic story, and this is where her sensitive, humble and straightforward, recycled, sad, and painful nature lies.

As the artist mentions: "I try to submerge a little deeper with each knot, to sink into myself," in the most Jonas Mekas sense, to get lost for the sake of getting lost, even more with a thread of hair, that binds her to the world.

Text

Nicolás Lange

/ dramaturge - writer - art curated

translation of Bruce Gibbons